In 2016, Taliban leader, Mullah Akhtar Muhammad Mansour, was killed in a U.S. drone strike in Pakistan’s Balochistan province. It was later revealed that he was returning from Iran when the drone strike was executed. Mansour’s death provided evidence for the growing bonhomie between Iran and the Taliban, as well as the deepening divide between the Taliban and Pakistan. Given the complicated history between Iran and the Taliban, this precarious alliance has raised several questions regarding Tehran’s intentions in Afghanistan. The fact is, the Taliban and Iran share two major interests in the region: a long-standing disdain for American presence in Afghanistan and a concern over the rise of Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP). This convergence of interests, coupled with the Taliban’s uneasy relationship with Pakistan, has enabled Tehran and the Taliban to look beyond their sectarian differences to cooperate in Afghanistan.

Tensions between the Taliban and Tehran

Iran and the Taliban have been traditional foes. Iran, a predominantly Shia country and the self-proclaimed leader and protector of the Shia sect, has long been at odds with the Taliban, which is a radical Sunni group. There have been several points in this decades-long history where tensions have ran high. The Taliban, when in power in Afghanistan, was suspected of providing support to anti-state Sunni rebels in Iran. Relations between the two reached a crisis in 1998 following the killing of Iranian diplomats and the massacre of Hazaras. The Hazaras, a predominantly Shia ethnic minority, have sometimes fled to Iran as refugees in order to escape the Taliban’s wrath.

Though Iran asserted its willingness the work with the United States, a sworn enemy, to challenge the Taliban, its efforts were ignored and U.S.-Iran relations have remained strained over strategic differences.

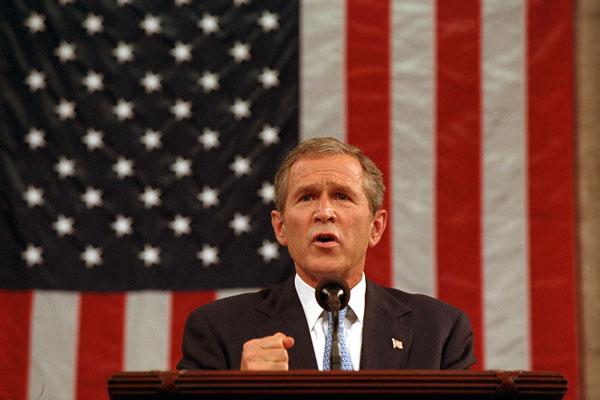

Tehran has in the past reciprocated these transgressions against its adversary. The Iranians, along with the Indians and Russians, countered the Taliban’s efforts to assert dominance over Afghanistan by providing support to the Tajik-dominant Northern Alliance between 1996 and 2001. In 2001, Iran supported the intervention by U.S. and North American Treaty Organization (NATO) forces in Afghanistan and provided intelligence against the Taliban. James Dobbins – the U.S. representative in the Bonn negotiations of 2001, which established the interim government after Taliban’s fall – has on several occasions emphasized Iran’s role in convincing the Northern Alliance to back the democratic government. Despite being named in the infamous “Axis of Evil” speech by President Bush in 2002 following a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) report alleging that Iran was pursuing nuclear weapons capability, Tehran continued to pursue avenues of cooperation with the United States to combat the Taliban, even going so far as to promise to train Afghan troops. Though Iran asserted its willingness the work with the United States, a sworn enemy, to challenge the Taliban, its efforts were ignored and U.S.-Iran relations have remained strained over strategic differences.

From Foe to Friend?

In recent years, Iran has displayed an increased willingness to aggressively pursue its interests in its neighborhood. Iran, through sectarian politics, filled the power vacuum in Iraq that resulted from U.S. withdrawal, having played a crucial role in defeating the Islamic State. Iran has also meddled in the domestic affairs of Lebanon, Palestine, and Yemen through proxy wars against arch rivals Israel and Saudi Arabia, even aligning with non-Shia groups, such as Hamas, to do so. As the epicenter of Shia Islam, this is noteworthy: Iran’s approach to its policies in the region have been shifting from identity-driven to interests-driven. This explains Tehran’s engagement with Taliban, which began to be understood after Iranian-made weapons intended for the Taliban were seized by U.S. forces in 2007. Thus, Tehran’s recent reorientation of how its strategic interests are pursued has opened the door for cooperation with the Taliban, especially given mutual disdain for U.S. presence and resistance to the rise of ISKP.

An Iran-Taliban alliance provides the Taliban an opportunity to secure a sincere partner through whom it can acquire the autonomy often lacking in Pakistani support.

Recent developments may influence increased cooperation between these unlikely allies. President Trump’s revised South Asia strategy has called for a surge in troop deployments to Afghanistan, which has further exasperated Iran’s leadership. Furthermore, the souring of U.S.-Iran relations over the decision of the United States to exit the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), along with the resulting sanctions, could influence closer ties between the Taliban and Tehran. The Trump Administration’s strategy towards Afghanistan and Iran creates a mutual enemy that is bound to hold this alliance together.

With the rise of ISKP, one of Iran’s major strategic concerns is the radicalization of the Sunni community in the border provinces of Sistan and Baluchistan. The minority Sunni and Kurdish communities, who have a long-standing history of anti-state rebellions in Iran, are viewed as soft targets for ISKP recruitments. Iran’s attempts to justify its ties with the Taliban has primarily revolved around the ISKP threat. The Taliban sees ISKP as a competitor that poses a threat to its long-term objectives in Afghanistan. Therefore, it makes strategic sense for the Taliban and Iran to work in tandem to neutralize ISKP.

A third reason for a Taliban-Iran convergence may be the Taliban’s increasing distrust of Pakistan. For instance, Iran’s willingness to facilitate cooperation between the Taliban and Russia makes Iran an appealing partner. At present, Russia – who, notably, has expressed major concerns over the growing threat from ISKP – is believed to be providing support to Taliban through Iran. Evidence suggests that the Taliban may perceive Iran as a more reliable ally than Pakistan, who has begun to face resentment for perpetuating “a patron-client relationship often kept on track through blackmail.” In fact, Seth G. Jones of the RAND Corporation stated Pakistan was “partly supportive of targeting [Mullah] Mansour.” Thus, an Iran-Taliban alliance provides the Taliban an opportunity to secure a sincere partner through whom it can acquire the autonomy often lacking in Pakistani support.

Conclusion

Iran’s intentions might prove detrimental for Afghanistan in the long run and clash with the Taliban’s nationalist interests eventually, but Tehran has proven to be a valuable ally for the Taliban for the immediate future. Iran provides the group legitimacy, arms, and flexibility to operate. Iran would prefer to tread carefully in Afghanistan, as it has in the past, and the Taliban will would like to remain wary of Iran. However, the current situation in the region—namely, sustained U.S. presence and the rise of the ISKP—renders it advantageous for both to pursue a partnership with one another to safeguard their respective interests.

***

Image 1: Adam Jones via Flickr

Image 2: Wikimedia Commons