This month marks 22 years since the nuclearization of India and Pakistan. These last 22 years have seen multiple Indo-Pak crises, each evoking at least some nuclear overtones. In the past year, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s August 5, 2019 decision to abrogate Articles 370 and 35A, revoking Indian-administered Jammu & Kashmir (J&K)’s special semi-autonomous status, has brought New Delhi and Islamabad to the crossroads of a permanent state of tension. Kashmiris in Indian-administered J&K are still under restrictions after almost 300 days, and the Line of Control has constantly been on fire.

The most recent Pulwama/Balakot crisis highlighted the evolving nature of India-Pakistan nuclear escalation. India believed that attacking Pakistan across the international boundary would test its resolve and call its nuclear bluff. However, the assumptions upon which India launched the Balakot strikes were flawed and based on its misunderstanding of two new realities: the changing and increasing indigenization of the Kashmir insurgency in Indian-administered Kashmir, and a misreading of Pakistan’s response options under Full Spectrum Deterrence. Pakistan’s demonstration of its resolve and credibility in the Pulwama/Balakot crisis likely addressed the second of these misunderstandings and could strengthen deterrence going forward. India’s continued lack of recognition of the changing reality of the Kashmiri freedom struggle, however, remains an issue that could presage continued Indo-Pak crises in the coming years. The result could be escalation, with each side willing to show high resolve and risk acceptance while ascending the escalation ladder.

Changing Nature of Insurgency in Kashmir

India’s continued lack of recognition of the changing reality of the Kashmiri freedom struggle remains an issue that could presage continued Indo-Pak crises in the coming years. The result could be escalation, with each side willing to show high resolve and risk acceptance while ascending the escalation ladder.

On February 14, 2019, in the town of Pulwama in Indian-administered Kashmir, Kashmiri resident Adil Ahmad Dar attacked a convoy of India’s Central Reserve Police Force, killing 40 security personnel. Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM) took credit for the attack. After an investigation, Pakistan rejected Indian claims of Pakistani involvement in the attack. The UN designated JeM chief Masood Azhar as a global terrorist a few months later while dropping any references to his linkage with the attack. However, going by Jaish’s own social media admissions, the linkage cannot be denied. Azhar had previously been released from Indian custody in 1999 in exchange for passengers of the hijacked Indian Airlines Flight 814. The point to consider is: why do groups like JeM continue to find space in J&K, and why are they successful in recruiting young Kashmiris? For how long will India turn a blind eye to its own structural vulnerabilities in Indian-administered Kashmir and seek an escape in “punishing” Pakistan?

To understand how the nature of insurgency in Kashmir has changed over time, it is important to grasp the difference between the symbolic Kashmir and the strategic Kashmir. From the 1990s onwards until the death of Burhan Wani in 2016, the symbolic Kashmir and the strategic Kashmir remained two separate entities. The symbolic Kashmir is “a place where larger national and sub-national identities are ranged against each other. The conflict in this Kashmir is as much a clash between identities, imagination, and history, as it is a conflict over territory, resources, and peoples.” In the strategic Kashmir, in contrast, “the military establishments on both sides of the border insist that Kashmir is critical to the physical defense of their respective countries.”

In the beginning of the armed insurgency in the Kashmir Valley in the late 80s and early 90s, challenging Indian control provided Pakistan an opportunity to alter the Kashmir status quo. Although Pakistan remained dismissive of its support in financing, arming, and training Kashmiris, scholars have noted that “the deepest roots of the insurgency could be found in India’s domestic affairs; Pakistani support for the militants was typically viewed as an important, but secondary factor.” Some other scholars also ascribe “the ferment to the disenchantment of young Kashmiris and increasing receptiveness to radical views when they found their rising educational and social aspirations thwarted and their path to economic and political empowerment blocked or manipulated.”

The indigenization of the Kashmiris’ struggle marked by rising anger and activity against Indian security forces could complicate Indian attempts to point the finger at Pakistan in order to justify escalation.

The death of Burhan Wani blurred the lines between these two Kashmirs. Born during the height of the insurgency in 1994, Wani was instrumental in turning a fading quest for independence into a Kashmiri Intifada through the use of modern means of communication. His death catapulted the resistance to another level, one that is dynamic, strong, and indigenous. Even Pakistan, perhaps, is not yet cognizant of the transformation taking place, whereby this indigenized struggle—fed by hatred for all things Indian and likely fueled by an RSS-BJP Hindutva nexus—may not require Pakistan’s material or moral support in the years to come. The symbolic and strategic Kashmir are heading for a clash that is likely to shape the Indo-Pak nuclear rivalry if these dynamics are not understood.

India’s future responses to subconventional activities in J&K are likely to be made difficult by these changing realities on the ground. The indigenization of the Kashmiris’ struggle marked by rising anger and activity against Indian security forces could complicate Indian attempts to point the finger at Pakistan in order to justify escalation.

Misreading Pakistan’s Capability, Resolve, and Thresholds

The second part of this new reality has to do with Pakistan shedding ambiguity about its resolve to retaliate and its relatively low nuclear thresholds. In an interview in 2002, Pakistan’s first Director General of the Strategic Plans Division, Lt. Gen. Khalid Kidwai, presented four red lines which, if violated, were to constitute Pakistan’s nuclear use scenarios. Since 2002, the ambiguity enshrined in these four thresholds has given India the comfort that as long as these red lines are not violated, it can push Pakistan.

The first Indian push came after the Uri attack in 2016. After militants attacked the 12th Infantry Brigade on September 18 killing 17 Indian soldiers, India blamed Pakistan, which denied any involvement. India then launched surgical strikes across the LoC. Pakistan, however, did not acknowledge the strikes and thus claimed there was no retaliation. The details of what the strikes accomplished remain a mystery.

Pakistan’s non-retaliation post-Uri gave India the impression that it might be in Pakistan’s interest to continue denying Indian surgical strikes as a strategy of face-saving. It also gave India false confidence that it had set a new standard for both domestic and international audiences. That changed in February 2019. As detailed by Retired Air Commodore Kaiser Tufail in his article for Pakistan Politico, after the failed Indian Air Force (IAF) strike inside Balakot on February 26, the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) put together a range of targeting options aimed at matching the IAF stand-off strike. PAF chose to strike near and around Indian military targets in the Poonch-Rajauri-Naushera Sector in Indian-administered Kashmir to showcase its capability and resolve, while stopping short of actually hitting Indian military targets. Escalation was not the purpose of the PAF’s strikes. In the dogfight that ensued, the PAF shot down an Indian MiG-21 Bison and captured the pilot. In a goodwill gesture, Pakistan returned the pilot to India, de-escalating the crisis.

Given India’s conventional superiority vis-à-vis Pakistan, demonstrating resolve through retaliatory strikes in itself was a strategic objective for Islamabad. Pakistan’s demonstration of its capability and resolve through retaliatory conventional strikes reinstated deterrence between the nuclear duo, indicated by the fact that a further round of escalation did not take place. What helped end the crisis, and which has received insufficient attention, was Pakistan’s rational decisionmaking, as exhibited by the early release of the captured Indian pilot and its careful choice of strike locations across the LoC.

The 2002 red-lines are no longer the benchmark of predictability associated with Pakistan’s nuclear behavior. Quid Pro Quo Plus, recently articulated by General Kidwai as Pakistan’s response to any attack in the future, is the new policy, with “Plus” being “the threat that leaves something to chance.” This marks a clear evolution in Pakistan’s strategic doctrinal thinking.

India-Pakistan Nuclear Rivalry in the Future: Deterrence Gains

It is important to learn the right lessons from the Pulwama/Balakot crisis. Indeed, it has important implications for the shape that the India-Pakistan nuclear rivalry could take in the future.

While there are concerns that both India and Pakistan can feel confident in playing rounds of escalation safely, the fear that either side may escalate is a deterrent in itself for any further escalation.

Vipin Narang has argued that “the prevailing narrative in South Asia is that escalation is easy, and easy to control. It appears that both sides believe they can now get significant kinetic shots in and walk away relatively unscathed. This is a dangerous misreading of Pulwama and its aftermath.” This is an oversimplification. Neither side in the crisis believed at any point that escalation was easy and controllable. Pakistan’s demonstration of its capability and resolve was rational and calculated. It needs to be appreciated that Islamabad’s response to India’s strikes—through its choice of targeted locations, the manner of their execution, and the release of the captured pilot—helped achieve crisis termination. Perhaps because Pakistan’s response was unprecedented and ran counter to most predictions that a conventionally-inferior, nuclear-armed state would escalate to the nuclear level relatively early on in a crisis,1 it has been hard for many scholars to give credit to Pakistan.

One can, then, point to some positive takeaways from the Pulwama/Balakot crisis.

New information about Pakistan’s capability and resolve communicated during the crisis—and India’s knowledge of it—could strengthen deterrence in South Asia. This is primarily because mutual vulnerabilities at non-nuclear levels came to the fore during this crisis. Such a scenario releases pressure on the defender to expand the scope and intensity of the crisis in its initial stages.

Similarly, Pakistan’s awareness of India’s ability to quickly deploy its naval nuclear assets to pressure Pakistan in tandem with its land and air forces would change Pakistan’s calculus of the Indian capability and resolve. Either way, it is a win for deterrence.

It is also worth mentioning that with nuclear weapons added to the mix, the balance of resolve rather than the balance of forces is what matters. Both India and Pakistan realize that escalation can happen even if neither side wants it to. Ideally, the realization of this unpredictability, which is operative in every crisis, coupled with the present balance of resolve, should have a stabilizing effect in any future crisis.

Going forward, India and Pakistan must each believe that the other is willing to run the risk of escalation to defend its strategic interests, irrespective of the conventional and nuclear balance. Kashmir is a strategic interest for both. The next crisis would be determined by how both states are able to strategically manipulate the risk of nuclear war by arranging threats and exhibiting greater levels of resolve, which would clearly determine the outcome of the crisis. Given the high stakes and concomitant commitment traps involved, it may not be difficult to manipulate the risks of nuclear dangers. To quote Robert Jervis, “[e]ven a slight chance that a provocation could lead to nuclear war is sufficient to deter all but the most highly-motivated adversaries.”2 While there are concerns that both India and Pakistan can feel confident in playing rounds of escalation safely, the fear that either side may escalate is a deterrent in itself for any further escalation.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

Image 1: Jack Zallium, Flickr

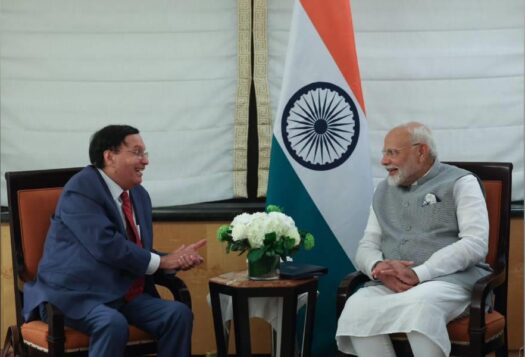

Image 2: Government of Pakistan