One indicator of the state of relations between India and Pakistan is the degree of peace or violence along the Line of Control (LoC) and the International Border (IB) in Jammu and Kashmir. The LoC, which functions as the de facto border between India and Pakistan, has been plagued by constant crossborder firing since the beginning of 2018, resulting in civilian and military casualties and damage to the border population’s homes, livestock, and other property. One of the most significant confidence building measures (CBMs) between India and Pakistan, a ceasefire agreement signed in 2003, is being violated at a pace so rapid it seems the agreement has been withdrawn without announcement. If there is such a thing as “war during peacetime,” it characterizes the current situation between India and Pakistan on the LoC and IB.

Though the current situation is dire, it is not a paradigm shift: since the signing of an informal agreement on the cessation of hostilities in 2003, border skirmishes have continued, fluctuating over the years and frequently making headlines when tensions are particularly high. Each time India or Pakistan violates the ceasefire agreement, there is a deleterious effect on bilateral diplomatic relations. At present, India-Pakistan relations are at a dangerous point: as border tensions escalate and diplomacy increasingly falls short, it is vital for the two rivals to renew the 2003 ceasefire agreement before the situation spirals into a serious conflict.

Devastating Impact of Ceasefire Violations

There is hardly any stretch of the LoC and the IB that has not seen some kind of ceasefire violations (CFVs). Border skirmishes in areas like the Rajouri and Poonch districts are an almost daily occurrence, while in February both armies exchanged heavy artillery on the LoC in the Uri sector of Kashmir for the first time in over a decade. The exchange of fire along these relatively calmer border areas is yet another warning sign that CFVs are growing more unpredictable and bilateral tensions are escalating. At present, there is no way of determining which areas are safer than others, with inhabitants living in constant fear and thousands fleeing their homes.

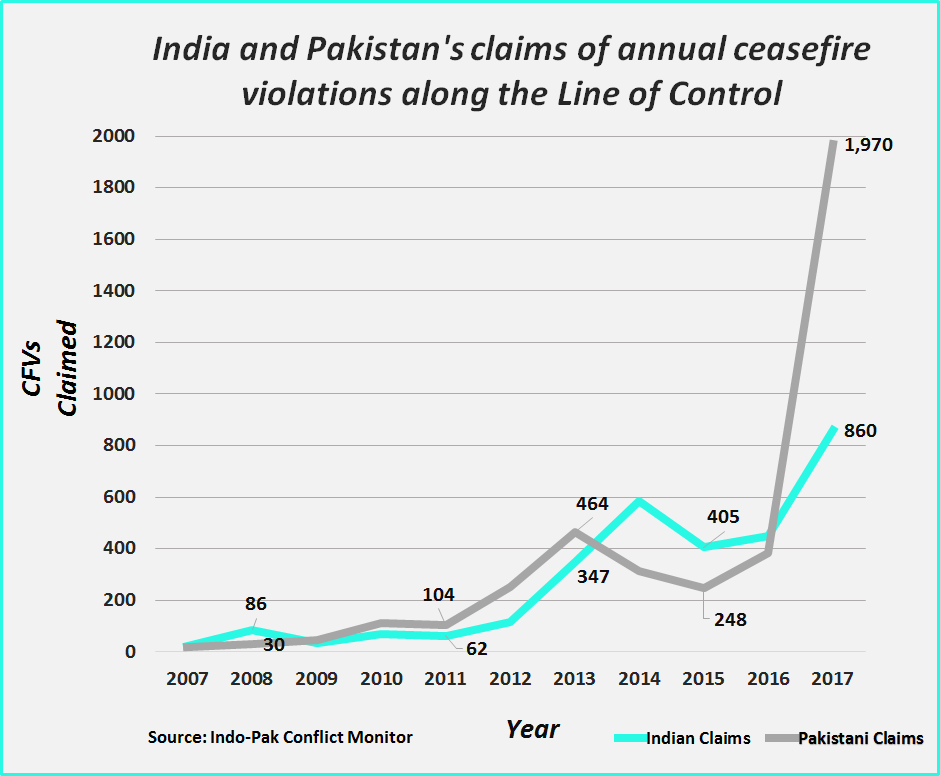

According to the government in New Delhi, 2017 saw 860 CFVs, a number that is over three times that in 2016. Countering India’s claims, Pakistan blamed India for 1,970 CFVs in the same year. The situation does not appear to be improving in 2018: Indian Minister of State for Home Hansraj Ahir told the Lok Sabha that Pakistan violated the ceasefire agreement 633 times in the first two months of 2018 while Pakistan’s foreign ministry blamed India for committing over 400 CFVs in the same period. Compared to previous years, claims of CFVs by both India and Pakistan have been skyrocketing, reaching their highest point in a decade in 2017 (see below).

Source: Indo-Pak Conflict Monitor

In addition to numerous military casualties, this “war during peacetime” has resulted in a multitude of noncombatant lives lost, maimed, and intermittently rendered homeless on the borders of the disputed Himalayan region. These people, who are already living difficult lives due to inhospitable topography and poor development, had been the direct beneficiaries of the 2003 ceasefire agreement. Thus, the blatant disregard for this agreement makes them the direct victims. Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti, in a recently held session of the state legislature, said 41 civilians were killed from 2015 through 2017 in Pakistani CFVs. For its own part, Pakistan has also reported a loss of civilian lives due to firing from India, including 16 deaths already in 2018.

Diplomatic Fallout

When Indian and Pakistani forces trade fire on the far-off mountains and hills of Jammu and Kashmir, its impact is felt in New Delhi and Islamabad when diplomatic sparring ensues through the summoning of envoys and release of public statements. Even when confidence building measures take place at the diplomatic level, unceasing military operations at the border seem to nullify the good that can come of these meetings. A recent instance is of the reported secret meeting between the Indian and Pakistani National Security Advisors in December, which could have led to a renewed peace process. However, there is a wider belief among pro-peace circles that the escalation of border clashes over the next month hampered the ability of these talks to have yielded positive results.

The continued clashes on the borders since last year have proved ominous for any expected dialogue initiative between the two countries. The border situation has actually stalled the process of peace talks, which was expected to be resumed through official or Track-II channels. In another recent example, India accused Pakistan of harassing its staff at the High Commission in Islamabad, triggering a new diplomatic row, with either side accusing the other of mistreating mission staff in their countries. Furthering these tensions, a war of words has added fuel to the fire that is the India-Pakistan conflict. Indian Home Minister Rajnath Singh, largely considered a “dove” in the hawkish Indian government, has threatened to double down on LoC firing, declaring “we have instructed troops to shoot limitless bullets to retaliate to a single fire on our territory from Pakistan.” On the Pakistan side, the Foreign Office has emphasized the human consequences of Indian CFVs as well as their destabilizing nature, stating they are “contrary to human dignity” as well as “a threat to regional peace and security [that] may lead to a strategic miscalculation.”

Curbing the Threat of Escalation

If the history of the India-Pakistan conflict is anything to go by, crossborder skirmishes may lead to full-scale conflict. Given that India and Pakistan have gone to war over Kashmir thrice before, it is important to consider how increasing border clashes spawn antagonism and bring the region closer to threat of nuclear war. The nuclear status of both states is pertinent when it comes to their relations regarding Kashmir, as demonstrated by Indian Army Chief Bipin Rawat’s statement that the army would have to call Pakistan’s “nuclear bluff” if asked to cross into Pakistani territory to carry out military operations due to a deteriorating situation along the border. In retaliation, Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), the media wing of Pakistan’s armed forces, warned that “India would be foolish to test Pakistan’s nuclear weaponry.”

Given the nuclear dimension of any India-Pakistan military standoff in Kashmir, neither New Delhi nor Rawalpindi should disregard the potential ramifications of CFVs. Academic Happymon Jacob, who has been part of Track-II peace processes with respect to Kashmir, warns that CFVs “have the potential not only to spark a bilateral military, diplomatic, and political crisis but also escalate any ongoing crisis, especially in the aftermath of terror incidents.” Aside from a preemptive diplomatic intervention, it is unclear how India and Pakistan can dampen the escalatory potential of CFVs when a crisis erupts. Thus, fearing that continuing and intensifying CFVs at the borders may provoke an uncontrollable military crisis, independent political commentators and peace activists from both countries have appealed to the powers-that-be to revive the ceasefire agreement and put a mechanism in place for military deescalation. Indeed, there is an immediate need in this conflict-ridden state to resolve these border clashes by renewing and strengthening the ceasefire agreement of 2003. Such an initiative will help to alleviate diplomatic tensions as well, as these tend to be exacerbated when there are soldier and civilian casualties at the LoC and IB.

***