Much Ado about the NFU

By: Tanvi Kulkarni

India’s nuclear no-first-use (NFU) policy is under public discussion again. This time, the buzz around the validity of the NFU pledge was set off by Defense Minister Rajnath Singh’s statement on August 16 at Pokhran in northwestern India. Speaking at an event commemorating former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee on his death anniversary, Singh commented: “Pokhran is the area which witnessed Atal Ji’s firm resolve to make India a nuclear power and yet remain firmly committed to the doctrine of ‘No First Use.’ India has strictly adhered to this doctrine. What happens in future depends on the circumstances. [sic]” Singh later also tweeted this comment from his official Twitter handle, dismissing chances of him being misquoted.

Instinctively, three questions merit discussion: What explains the timing of Singh’s statement? Has India given up its NFU pledge? Does the NFU still serve India’s national security and strategic interests?

The defense minister’s comment comes at a critical juncture when India’s relations with Pakistan are at an all-time low, post the Pulwama terrorist attack and the Balakot airstrikes, and when the Indian state is redefining its relationship with its territories of Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh. The occasion and location of Singh’s statement also have great significance for India’s identity as a nuclear weapons power—Pokhran is where India conducted its 1998 nuclear tests, authorized by Vajpayee. The last time a serving cabinet minister of India made a similar reference with regard to the NFU pledge was then-Defense Minister Manohar Parrikar, in November 2016, two months after the post-Uri surgical strikes conducted by the Indian army. While Parrikar qualified his comments as his own thinking and the Ministry of Defense also clarified that it was the minister’s “personal opinion,” Singh has given no such disclaimer. Given that both comments were made by government officials serving in India’s highest decisionmaking group, the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS), and in close proximity to periods of escalated tensions with Pakistan, the seriousness and signaling (both domestic and international) implicit in these statements cannot be shrugged off.

That the existing leadership would now want to review the utility of the NFU pledge is a reflection not only of its preference for a muscular national security policy but also of the changes in the strategic landscape in Asia.

Having said that, nothing in the defense minister’s statement suggests that India has given up its NFU pledge; in fact, it reads as the bare-bones of a nuclear policy and doctrine that has been intentionally ambiguous about the NFU. India’s nuclear doctrine defines the NFU as a posture of retaliation only. The civilian leadership in India has consistently declared NFU as a political commitment without spelling out the nature of nuclear retaliation. The NFU policy was first formally “modified” by the government in 2003 by adding the caveat of nuclear retaliation against a chemical and biological attack on India or its forces operating within or outside Indian territory. Thus, the Indian nuclear doctrine is subject to review and not immutable even though subsequent Indian governments since 2003 have neither felt the need to publicly revise the doctrine nor give up on the NFU pledge altogether.

NFU is a political declaration whose credibility is almost impossible to fully prove. India’s NFU policy has been subject to wide domestic public debate since 1999. Ambiguity in defining the NFU has allowed for multiple appropriations of the policy within India’s strategic community, especially with regard to its technical and operational ends. The NFU was adopted as a logical corollary to India’s credible minimum deterrence doctrine, indicating a relatively relaxed nuclear force posture. Advocates of the NFU argued that India does not require threatening its adversaries with a first use posture to address the challenges of its security environment. That the existing leadership would now want to review the utility of the NFU pledge is a reflection not only of its preference for a muscular national security policy but also of the changes in the strategic landscape in Asia. For instance, an emerging arms race involving the United States, Russia, and China in Asia would have implications for India’s strategic calculations with regard to nuclear and conventional force structures. Periodic reviews and even revisions to policy are imminent and even useful as the strategic and security environment alters.

Since the Indian NFU policy happens to be at the center of renewed debates on nuclear strategy, it is a good time to impress upon Indian decisionmakers that a robust nuclear posture against emerging security threats requires tightening the loose ends of the nuclear doctrine rather than retiring the NFU policy entirely.

***

RIP No First Use

By: Sitara Noor

Defense Minister Rajnath Singh’s latest statement indicating a potential change in India’s no-first-use (NFU) commitment has reignited debate on the sanctity of India’s NFU pledge. On the first anniversary of the death of former Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Singh tweeted: “Pokhran is the area which witnessed Atal Ji’s firm resolve to make India a nuclear power and yet remain firmly committed to the doctrine of ‘No First Use’. India has strictly adhered to this doctrine. What happens in future depends on the circumstances. [sic]”

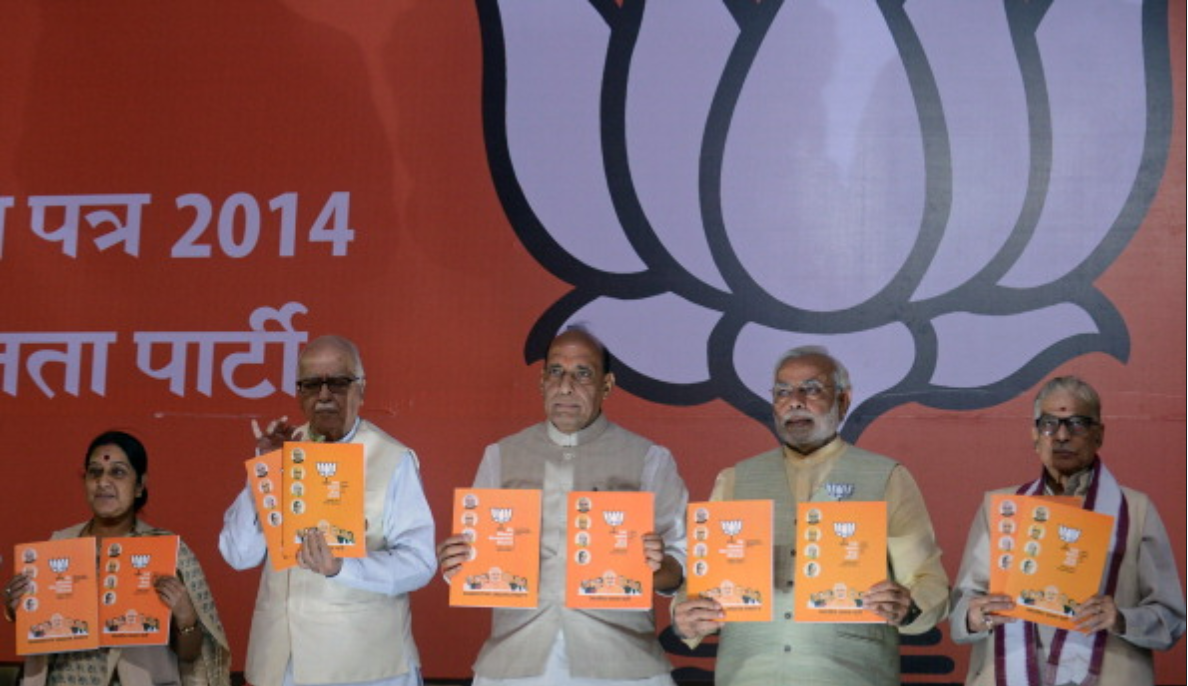

This is yet another example in a series of statements by current and former Indian officials that have raised questions on the sanctity of the country’s NFU pledge since the BJP proposed a revision of India’s nuclear doctrine in its 2014 election manifesto. After former Defense Minister Manohar Parrikar made comments at a book launch in November 2016 suggesting that India should rethink its NFU pledge, a spokesperson from the Indian Ministry of Defense labeled it as the minister’s “personal opinion.” However, this latest remark by Singh seems to have been carefully choreographed and presumably authorized by the government. Neither an official repudiation nor a clarification followed from the government, distinguishing it from previous statements on this issue by the former defense minister, former national security advisors, and other scholars. Singh’s remarks thus represent the first official signal of a potential change in India’s NFU policy in future.

Although Singh’s latest statement has effectively killed India’s NFU pledge, it may not lead to any official change in India’s declared nuclear doctrine in the near future, for two reasons. Firstly, the NFU pledge carries political dividends for India and has helped it earn the status of a “responsible” nuclear armed state without being a signatory to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.[…] Secondly, any official declaration of first use is bound to face credibility challenges in the absence of major changes in India’s force posture.

Some Indian scholars have attempted to downplay the statement by focusing on its first part where Singh emphasized that the doctrine of nuclear no first use has been “strictly adhered” to until now. Nonetheless, any such pledge would direct future policy during peace and wartime and past adherence does not guarantee its future sanctity. Other analysts have argued that this statement indicates a shift from no first use to ambiguity. However, it is important to note that even an absolute NFU pledge would be viewed with a certain degree of doubt by the adversary due to its non-verifiable nature. Adding deliberate ambiguity would only confirm the doubts of the adversary of the fallibility of the NFU pledge. That is why Pakistan has never accorded any credence to India’s NFU pledge and considered it a hollow statement aimed at garnering political dividends, especially after India’s 2003 official nuclear doctrine added caveats to the absolute NFU pledge of the 1999 draft nuclear doctrine. Commenting on Singh’s statement, Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi asserted that India’s NFU pledge is “non-verifiable and cannot be taken on face value, particularly when developments of offensive capabilities and force postures belie such claims.” He further stressed that Pakistan would maintain its policy of credible minimum deterrence in response.

Although Singh’s latest statement has effectively killed India’s NFU pledge, it may not lead to any official change in India’s declared nuclear doctrine in the near future, for two reasons. First, the NFU pledge carries political dividends for India and has helped it earn the status of a “responsible” nuclear armed state without being a signatory to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. It has helped India secure nuclear deals with various countries after gaining a Nuclear Suppliers Group special waiver. Secondly, any official declaration of first use is bound to face credibility challenges in the absence of major changes in India’s force posture. Even if India is shifting its declared massive retaliation posture to preemptive counterforce targeting, as suggested by some analysts, India’s current force posture is not yet equipped to carry out a successful preemptive counterforce attack on Pakistan. Despite India’s increasing investment in technologies such as precision-strike weapons, new cruise and ballistic missiles, ballistic missile defense, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) potentially usable in a counterforce attack, India cannot claim to have a robust and failsafe system that can disarm Pakistan’s entire nuclear attack capability.

Nonetheless, this is not an ordinary statement, given India’s behavior during the recent Pulwama/Balakot crisis where it deployed its nuclear missile-armed Arihant submarine and was supposedly ready to launch a missile attack on Pakistan. In the backdrop of ongoing tensions, Pakistan has termed Singh’s statement “shocking and irresponsible” as it represents a nuclear threat to Pakistan as well as to China, albeit to a lesser extent. Out of many lessons learnt from the Balakot episode, the most important one may be that escalation can happen in an unexpectedly rapid manner due to miscalculation. In an increasingly volatile security environment, statements such as Singh’s add to the risk of miscalculation and in turn are bound to generate greater regional instability.

***

Click here to read this article in Urdu.

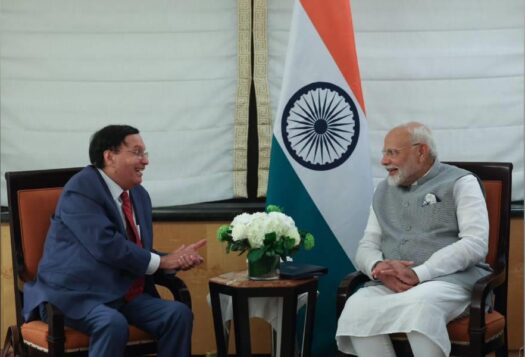

Image 1: Rajnath Singh via Twitter

Image 2: Raveendran/AFP via Getty Images