The cancellation of a meeting between the Indian and Pakistani foreign ministers that was to be held on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) provided context for the Indian army chief’s statement that, “there is a need for one more action [surgical strike].” However, he later added that surgical strikes are not the only option for decisive action if India is confronted with a Pakistani provocation. On cue, the Pakistani military spokesperson claimed his military is ready for war, rationalizing that war happens when either side is unprepared for it and Pakistan’s information minister took care to remind India that Pakistan is a nuclear power.

The annual war of words between the two sides continued at the 73rd UNGA session in New York with the two foreign ministers using their respective addresses to trade barbs, followed by officials exercising the right of reply. While India accused Pakistan of harboring terrorists, Pakistan declared that India preferred “politics over peace.” This period of rhetoric, brought on by the brutalization in Kashmir in the killings of special police officers and a Border Security Force trooper, framed India’s end of September Parakram Parv (celebration of valor) exhibition commemorating the second anniversary of the 2016 surgical strikes.

If the ratcheting up of rhetoric now is any indicator, the subcontinent is closer, yet again, to another crisis, especially since the buffer of meetings and talks–that could serve as an intervening step in being called-off–is no longer there.

However, the singular aspect of the surgical strikes episode missing in the celebrations across India was its cognizance of escalatory possibilities. The surgical strikes post the Uri attack were deliberately kept limited, a feature emphasized early in a press briefing by India’s military operations chief. For its part, Pakistan, aware that the onus was on it, wisely pretended that the trans-Line of Control (LC) raids never took place. If the ratcheting up of rhetoric now is any indicator, the subcontinent is closer, yet again, to another crisis, especially since the buffer of meetings and talks–that could serve as an intervening step in being called-off–is no longer there.

In case the lesson learnt from the surgical strikes is to apply to the next round, then India shall likely keep any substitute options for surgical strikes equally limited. The problem is that the Pakistani army cannot use its earlier alibi twice over. Once bitten, it has surely war gamed its reaction. It follows then that there are two possibilities: the first is Pakistan, duly prepared, drawing blood. The second is Pakistan, caught flatfooted yet again, forced to up-the-ante.

In the first case, the onus of upping-the-ante would be on India. Having milked the surgical strikes anniversary for political dividend, the government would not like egg on its face as it goes into elections. Irrespective of the military’s itch to get even and goading by the long-compromised media, it will have its own political compulsions to “do something.” In the second case, to save face with its domestic constituency, Pakistan’s army may make a retaliatory move or two. India would then put up its guard and ward the counter punches off, but these moves would constitute steps towards a slippery slope. Both would edge towards a slippery slope, with an eye to catalyzing intervention by the international community. The expectation is that, Donald Trump’s isolationism notwithstanding, a worried United States, which has political heft with both countries, and China, which can work better on Pakistan, will be on hand to help de-escalate.

This is a happy ending of a script going from crisis to confrontation, in which both take home something from running the risk. Pakistan gets to highlight its pet flogging horse, the Kashmir issue, and India manages to inflict pain directly on Pakistan for its temerity. Its likelihood depends on the validity of each sides’ self-assessment of “escalation dominance.” Though usually associated with nuclear warfighting, the term can be used to imply the ability to prevail at a particular level along the spectrum of conflict: subconventional, conventional, and nuclear.

In view of Pakistan’s obfuscation of the conventional-nuclear divide in its introduction of tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs) into the picture, India seems to have broadened its subconventional options lately. This may explain surgical strikes and any variants up its sleeve.

To illustrate, India has endeavored over the past decade and a half to hone its conventional edge. This has been to signal that since India has the advantage at the next higher level, Pakistan would be better advised not to test its tolerance threshold in its proxy war at the subconventional level. Pakistan’s turn to “full spectrum deterrence” is an effort to deny India escalation dominance at the conventional level. In view of Pakistan’s obfuscation of the conventional-nuclear divide in its introduction of tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs) into the picture, India seems to have broadened its subconventional options lately. This may explain surgical strikes and any variants up its sleeve.

India has also embarked on rekindling escalation dominance at the conventional level. It has an army restructuring program afoot, reportedly to be signed off at the army commanders’ annual autumn conference this month. Additionally, early in his tenure, India’s army chief, for the first time, acknowledged the existence of the Cold Start Doctrine, a limited war concept that is the army’s doctrinal response to the overt nuclearization of the subcontinent. He appears to now be reconfiguring the army to be able to measure up to the challenges of a potentially nuclear conflict—the army chief emphasized the necessity of doing this by confessing that the Indian army is only prepared to “fight previous wars.” Apart from the other features of the reforms, such as the optimization of manpower and the equivalence of army ranks with civilian peers, the restructuring shall enable the army to work its Cold Start Doctrine better.

While Pakistan has earlier obfuscated the nuclear-conventional level divide to trump India’s conventional advantage, India appears to now be obfuscating the subconventional-conventional level divide in order to provide itself options up the escalatory ladder, but below the nuclear threshold.

Part of this reform is the reported doing-away-with of divisional headquarters of pivot corps to be replaced by composite and integrated brigades. Prior to the advent of nuclear weapons in the armory, limited offensives were with division-sized forces. However, with the Cold Start Doctrine kicking in, these were to be executed by integrated battle groups (IBGs). The size of these IBGs was not in the open domain, but the Pakistani response of going in for TNWs suggests that the IBGs were sufficiently heavy to justify such a response. Thus, the reform under discussion will likely enable sprightly and multiple limited thrusts into Pakistani territory by up to armored brigade level forces, so as to make the Pakistani resort to TNWs difficult to both justify and operationalize. This brings the conventional level back into play, while preserving India’s punch in the form of strike corps that, according to media commentary, are not subject to the restructuring. These remain handy for conventional deterrence and in case Pakistan ups the ante, either through conventional forces or nuclear weapons, India can pursue operations even under a war gone nuclear.

Thus, India’s military restructuring promises to expand the scope for moving from crisis to confrontation. Its deterrent value is in being able to take a step closer to the slippery slope.

The tussle is between India pulling up the window for military options below the nuclear level and Pakistan thrusting down the nuclear awning over it. While Pakistan has earlier obfuscated the nuclear-conventional level divide to trump India’s conventional advantage, India appears to now be obfuscating the subconventional-conventional level divide in order to provide itself options up the escalatory ladder, but below the nuclear threshold.

In this doctrinal tennis match, the ball is now in Pakistan’s court. What is certain is that its answer over time and India’s response will keep the ball dangerously in play for as long as the two countries keep off the table.

***

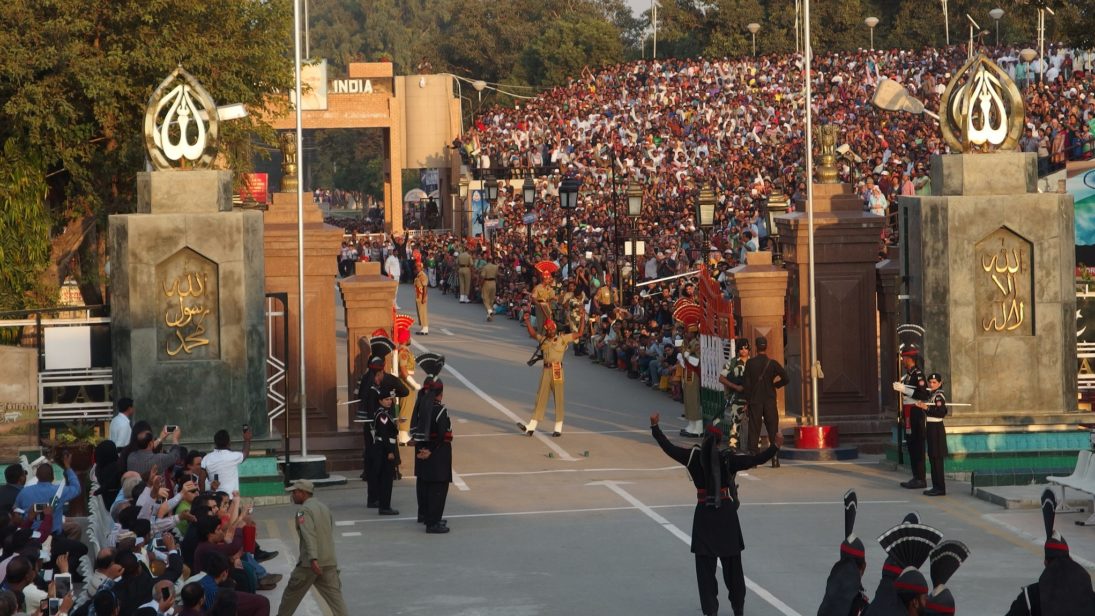

Image 1: Guilhem Vellut via Flickr Images (cropped)