The Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) plenary in Bern last month didn’t feature any movement on India’s membership. Any further discussion regarding membership for non-Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) states has been postponed to the meeting later this year in November. The short statement issued at the conclusion of the plenary noted that the group held discussions on “the issue of ‘Technical, Legal and Political Aspects of the participation of non-NPT states in the NSG” and “continued to consider all aspects of the implementation of the 2008 Statement on Civil Nuclear Cooperation with India and discussed the NSG relationship with India.” Two things held up discussion on Indian membership: active opposition by China and the lack of facilitation by the United States.

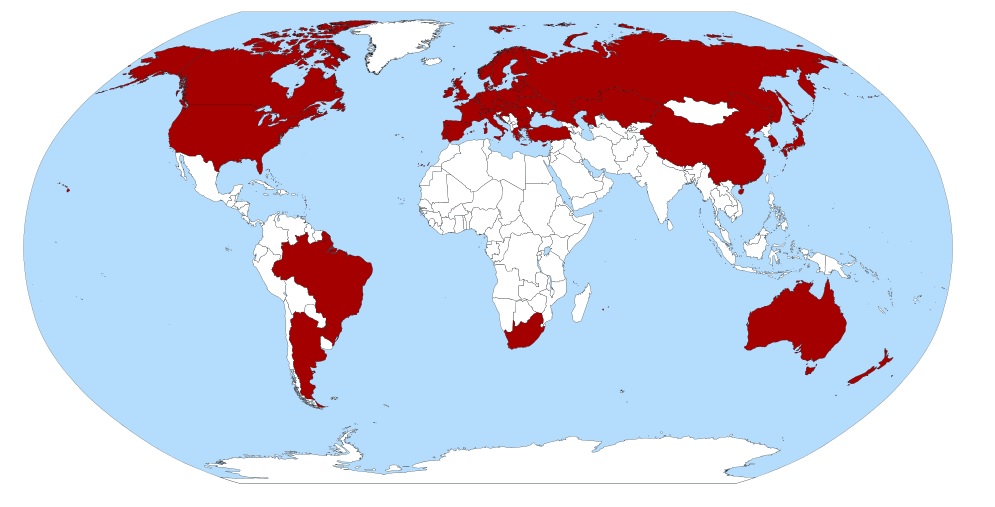

India has invested some very proactive diplomacy in its NSG bid. It appears to be moving towards securing the support of several countries that once were on the fence – Brazil and New Zealand, for example, have been reported to express their understanding of India’s position, although they’ve stopped short of offering unequivocal backing. China, among a handful others such as Austria and Ireland that continue to hold out, opposes India’s entry.

The first obstacle, therefore, is China. This is deliberate opposition. China claims to lay emphasis on the NPT’s centrality to gain membership of the NSG. It believes all countries that are not part of the NPT must be subjected to a non-discriminatory criteria-based, two-step approach reached by consensus among all 48 members of the group. But as I have argued before, China’s decision to hold up the NPT card in opposition to India’s membership is more strategic than it is principled. China could be hoping for one of two conclusions by hyphenating India’s membership with Pakistan’s. One, keep India out entirely if the group by consensus decides to not allow entry based on the latter’s non-proliferation credentials. Two, if indeed both become members, Pakistan will gain the same symbolic legitimacy that India seems to be seeking in recognition of its responsible nuclear status through the NSG. The added benefit of this for China is the reduced value of this legitimacy for India if Pakistan also becomes a member.

China does not view India as an equal. If India were to acquire NSG membership, it would sit at the same high table as China—one of the P5—and have access to decision-making regarding future members, one of whom could be Pakistan. Keeping India’s membership tied to Pakistan’s, therefore, not only delays consensus building, it also addresses the issue of a possible Indian ‘no’ vote on Pakistani entry once it is a part of the group.

Current India-China bilateral tensions further buttress China’s opposition. In June, China’s Assistant Minister of Foreign Affairs Li Huilai said: “About the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) it is a new issue under new circumstances and it is more complicated than previously imagined.” While he did not explain what he meant by “new circumstances” complicating the picture, it could have been a reference to India’s decision to stay out of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which has not gone down well with the Chinese. This was then. Now, after the Bern plenary, in an accumulation of brewing bilateral rifts, India and China are locked in a military stand-off in Doklam. Although India and China have in the past been able to somewhat insulate their bilateral diplomacy from border disagreements, China no longer seems willing to keep the two tracks separate, especially when it plays to its advantage. Highlighting as far back as June that there were issues that appeared unrelated to the NSG strengthening China’s disapproval of India’s entry into the group, and more recent developments such as Doklam, make the prospect of a discussion on NSG membership now untimely. The bottom-line is that there are other much more important bilateral issues to be dealt with first.

The lack of a clear U.S. strategy to facilitate discussion on Indian membership seems to have been the second deterrent. The Obama administration put its weight behind India’s application for membership, reportedly lobbying on its behalf. It appears that while the policy of backing India’s bid will not change under the Trump administration, there has not been much thinking about the extent of diplomatic capital it will be willing to deploy to secure Indian membership. To decide and execute the course of U.S. foreign policy, the house must first be put in order. With the U.S. Department of State under Rex Tillerson undergoing significant reorganization, the chances that India’s NSG membership has been discussed as a priority agenda item seem rather slim. This lack of a coherent U.S. strategy to facilitate Indian NSG membership seems to have played out as inaction at the Bern plenary, precluding movement on the subject at this stage. In addition to having a set of foreign policy challenges that would necessarily deprioritize India and the NSG—North Korea, the Islamic State (IS), Russia, China, Iran, to name but a few—there is also the question of whether the United States would be willing to take on China on India’s behalf. Meetings with policymakers and analysts in Washington, D.C. over the past ten days corroborate these conclusions.

With China’s increasing opposition compounded by rising China-India bilateral tensions, and U.S. foreign policy attention being occupied by a range of other high-profile challenges, a successful Indian NSG bid looks set to be put in cold storage in the near-term. Countries like Brazil and New Zealand have no reason to display a firmer commitment to a particular course of action beyond the so-called positive signals they have already sent to India regarding its membership; nor do those that oppose, like Austria and Ireland, have reason to seek to debate the issue, when both China and the United States, each for a different set of reasons, hold up India’s entry.

***

Editor’s Note: Click here to read this article in Hindi

Image 1: Nuclear Suppliers Group website

Image 2: Kim Kyung-Hoon-AFP, via Getty Images