On his maiden visit to India as president earlier this year, Donald Trump declared before the packed stands of Ahmedabad’s Motera Stadium that “together, we will defend our sovereignty, security, and protect a free and open Indo-Pacific region[…].” This marks one more in a long line of ambitious statements U.S. leaders have made regarding United States-India cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. However, on multiple occasions, India has failed to meet U.S. expectations on defense and security collaboration due to a combination of miscommunication and misperception over what India is willing and able to contribute to a shared Indo-Pacific vision. While the United States and India have both professed commitment to a free, open, and inclusive Indo-Pacific region that upholds the current rules-based order, India’s efforts towards this may not come in the form that the United States desires.

The United States expects to partner closely with India in the Indo-Pacific, given that India is also concerned about a rising China. However, unlike the United States, India faces threats from China not just in the maritime domain, but also on its land border. Despite grand pronouncements of India’s growing role as a counter to China in the Indo-Pacific, it seems likely that for the foreseeable future, India will continue to prioritize the threat that China poses to its land borders rather than in the maritime domain. Indeed, depending on the outcome of the ongoing standoff between India and China, New Delhi’s perception of Beijing as a continental threat and India’s emphasis on funding its military capacity along the border may only be reinforced. India’s strategic prioritization is demonstrated by the balance of its land and maritime threat perceptions, which is also reflected in its naval modernization funding. U.S. policymakers have to reckon with the consequences this Indian strategic outlook will have for the United States’ strategy in the Indo-Pacific, and find ways to work within India’s means to leverage the partnership to achieve U.S. regional objectives.

India’s Perceptions of China at Land and at Sea

The salience of China in India’s threat perceptions is indicated by the fact that Beijing’s development of nuclear weapons was a significant factor in New Delhi’s drive to acquire a nuclear capability. More recently, concerns about the military threat from China have led India to develop or seriously consider a host of platforms and capabilities at both land and sea, such as the Agni-V, the BrahMos cruise missile, the K-5 submarine-launched ballistic missile, and an anti-satellite missile. However, China’s defense modernization and the significantly lesser resources at India’s disposal have pushed New Delhi to assess whether Beijing poses a greater risk on the land border or in the Indian Ocean. And it seems that at present, India has chosen to continue prioritizing the threats to its land border.

The actively contested nature of the India-China border, as shown by the recent clash in the Galwan valley, and the historical memory of the 1962 Sino-Indian war both intensify New Delhi’s threat perceptions of China on land. Frequent Chinese aggression on the Line of Actual Control over the last few years underlines India’s concerns that China is undermining its core interests of territorial integrity and sovereignty—the preservation of which has always been a top priority, particularly in the context of the struggle for decolonization. Additionally, the Indian military and political establishment’s strategic assessment of Beijing as revisionist on its land border and its close military partnership with Islamabad have led to a greater concern that Pakistan and China are encircling India. Further, analysts suggest that India considers Chinese efforts to strengthen military capabilities and infrastructure on the border as shifting the balance of power, rendering India at risk of being unable to credibly deter or effectively respond to another Chinese fait accompli of the kind seen during the Doklam standoff. India has demonstrated this concern by working to build up its own infrastructure along the border and continuing to increase funding for the Border Roads Organization. India has also worked to improve the functioning of its new operational model on the border. This has been part of a slow-going, but sustained effort to diminish the imbalance between the two sides. Thus, the combination of India’s acute concerns about its territorial integrity and its strategic assessment of Chinese capabilities and intentions makes India’s land borders a high priority.

Frequent Chinese aggression on the Line of Actual Control over the last few years underlines India’s concerns that China is undermining its core interest of territorial integrity and sovereignty […] Additionally, the Indian military and political establishment’s strategic assessment of Beijing as revisionist on its land border and its close military partnership with Islamabad have led to a greater concern that Pakistan and China are encircling India.

In comparison, India perceives the threat China poses in its maritime domain as potentially targeted at its sea lines of communication (SLOCs), and fears that China may try to encircle it through a “string of pearls” strategy that utilizes China’s relationships with other regional states. While these are certainly long-term concerns for India, most analysts agree that, at present, these threats are seen as relatively underdeveloped and unlikely to threaten India’s core strategic interests. This is because China’s sea denial capabilities, which could hold India’s SLOCs at risk, are still limited. Furthermore, India is able to lean on the United States and other regional partners to help protect trade routes that are commonly used by all in the region.

Additionally, China’s relationships with Indian Ocean Region states, beyond Pakistan, have not evolved to the point of becoming reliable partnerships that could threaten India’s security. As well, India’s efforts to strengthen ties with its neighbors through investments in diplomacy, rather than a more militaristic strategy, have shown some signs of success. Ultimately, India’s actions suggest that it perceives China’s growing presence in the maritime domain as a long-term challenge to India’s status as the regional political hegemon rather than a pressing threat that could break out into direct confrontation or conflict. Therefore, for India, these threats seem minor compared to the more urgent risks on its border with China.

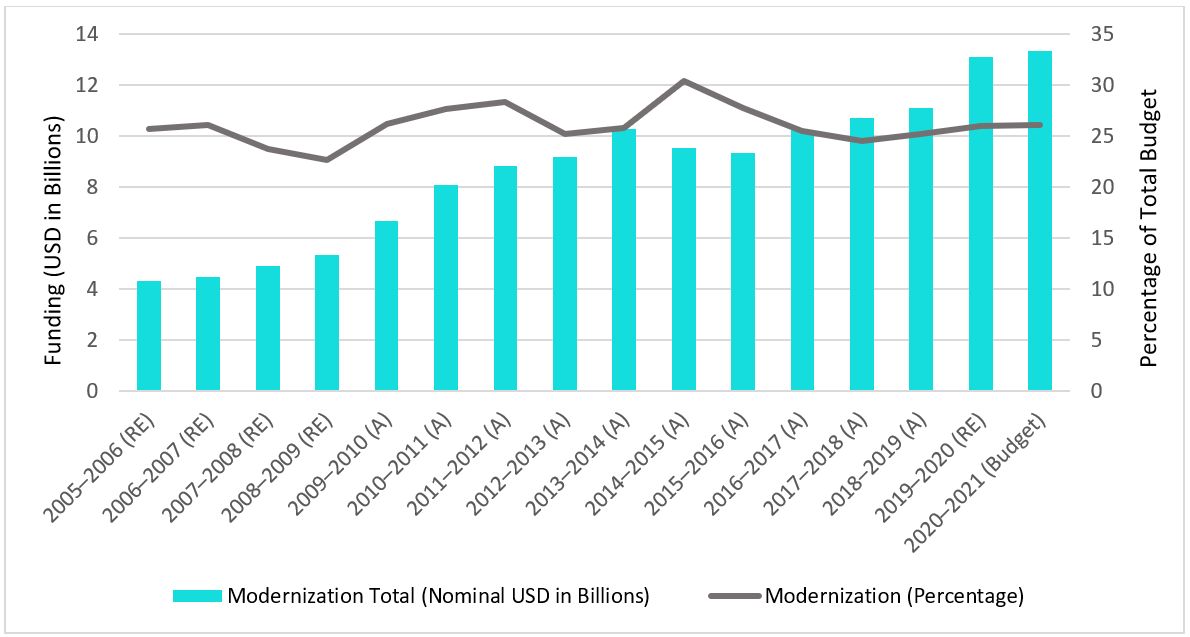

Further evidence of the lower priority that India places on the maritime domain can be seen in its modernization funding for the Indian Navy (IN). As Figure 1 indicates, the IN has received a relatively flat proportion of the military’s modernization budget, which suggests that the maritime domain has not become more of a priority over the last 15 years. Indeed, recent reporting further suggests this is the case. Given the lack of an increase in proportional funding for naval modernization, India’s perception of the maritime domain as a whole, and therefore the threat China poses in it, seems to have remained static. Despite India’s proclaimed move to align with the United States on the Indo-Pacific vision as a counterweight to growing Chinese regional influence, India has not shifted towards a greater emphasis on naval modernization. This has stark implications for the efficacy of the United States’ Indo-Pacific strategy.

Figure 1: Indian Navy Modernization Budget (2005-2020)1

Impact on the Implementation of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy

Based on the composition of India’s threat perceptions vis-à-vis China, the United States should have realistic expectations for what role India can play in the Indo-Pacific. India is not likely to have the capacity for sea control in the Indian Ocean anytime soon and it is still a ways away from close military-military relationships with its partners in Asia, due to the pace of its naval modernization and its strategic prioritization. Therefore, the United States needs to modulate near term expectations of India’s contribution to its Indo-Pacific strategy.

The United States should also be willing to work more with India on its other security priorities in the maritime domain. India perceives what the United States would consider to be non-traditional security issues—such as relationship building with littoral states, anti-piracy operations, and disaster management—as critical issues in this sphere.

The United States should also be wary of reading too much into India’s maritime engagement as it seeks to understand whether India will balance against China. Indian actions designed to respond to China may not come in the domain that the United States expects, as India remains focused on the security and stability of its borders. However, this does not mean India will ignore the maritime domain, and the United States and India should be willing to leverage their respective comparative advantages. India’s advantageous geostrategic position renders it well suited to play an important role in Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA), which it has taken steps to do, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), which would help supplement what could be a more slimmed down U.S. Navy.

The United States should also be willing to work more with India on its other security priorities in the maritime domain. India perceives what the United States would consider to be non-traditional security issues—such as relationship building with littoral states, anti-piracy operations, and disaster management—as critical issues in this sphere. Past U.S. efforts to engage with India on these priorities have strengthened the relationship and demonstrated that the United States values India as a partner. As Washington interprets New Delhi’s maritime priorities, it needs to be clear-eyed about how India will distribute its finite resources given its hierarchy of threats and recognize that the trade-offs India has chosen to make are not likely to change anytime soon.

***

Image: U.S. Navy via Flickr

- All budget data was collected from https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/previous_union_budget.php under “Capital Outlay on Defense Services.” “Modernization” refers to capital outlay. Percentage data is as a proportion of the sum of the Army, Air Force, and Navy’s modernization budgets. (RE) is revised estimate of the budget, (A) is actual spending, (Budget) is initial budget. All calculations and detailed sources are available here.