On July 7, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voted on the text of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The treaty prohibits the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons by signatory nations and bans developing, testing, producing, manufacturing or stockpiling nuclear weapons. It also bans the transfer and receiving of nuclear weapons and prohibits states from stationing, installation or deployment of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices in their territory or at any place under their jurisdiction or control (Article 1).While most South Asian countries voted in favor of this ban, two populous, nuclear-armed states, India and Pakistan, abstained from the vote. These abstentions indicate that greater public awareness of the goals of disarmament is required in both countries. However, this may prove to be a challenge given that nuclear weapons in Pakistan and India are still seen as symbols of national pride.

South Asia and the Prohibition Treaty

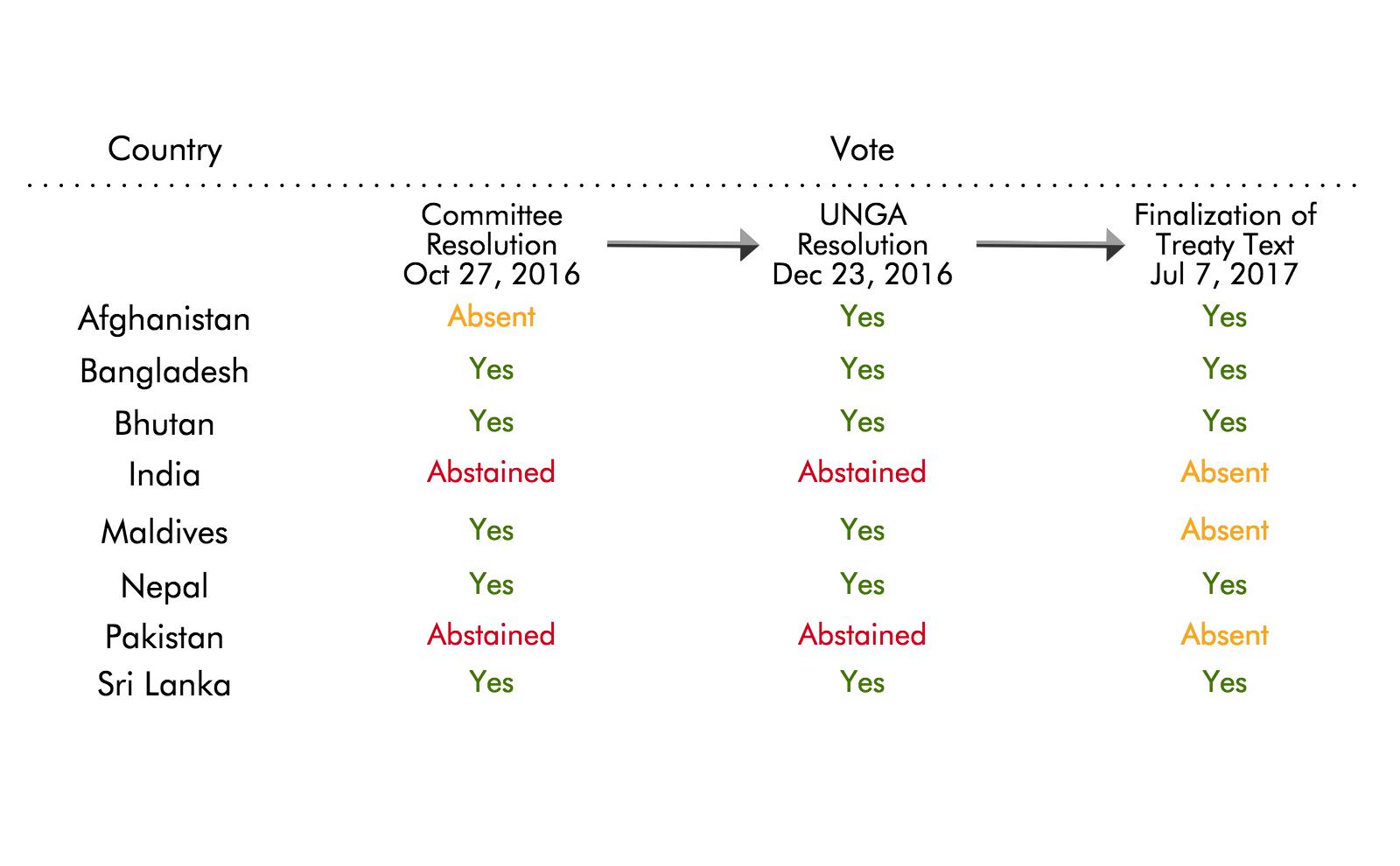

From South Asia, Nepal, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh voted in support of the treaty text. At three crucial stages, most states from the region maintained consistency in their stance on the issue (refer table below). Both India and Pakistan abstained from the process, claiming the treaty does not inspire confidence due to the lack of verification mechanisms and the absence of considerations of national security. Both countries refused to consider the Treaty to be a furtherance of the development of customary international law constraining the use of their nuclear weapons.

In 2013, India’s former Foreign Secretary Shyam Saran denied assertions that India’s nuclear weapons program was driven by “notions of prestige or global standing rather than considerations of national security.” Even if Saran is correct and India’s national security considerations drove the development of its nuclear weapons program, the public has come to consider nuclear weapons as primarily a prestigious achievement, essential for India’s global reputation as an emerging power, rather than only a national security tool. According to a Lowy Institute poll from 2013, 79 percent of Indians believe that nuclear weapons are important for achieving India’s foreign policy goals. Similarly, Pakistan’s nuclear weapons also serve as a symbol of prestige apart from pure nuclear deterrence utility.

Nuclear Weapons as Symbols of Prestige

This deification of nuclear weapons legitimizes their existence by intimately linking them with national pride. In such an environment, any opposition to the proliferation or development of nuclear weapons is deemed unpatriotic and against national interests. This narrow-minded rhetoric further weakens citizen participation in debates regarding nuclear weapons. Ultimately, this prevents the democratization of the debate and concentrates power further in the upper echelons of the state.

As such, the global discourse must change so that nuclear weapons are no longer viewed as a pillar of national prestige. The conflation of nuclear weapons with global power likely has its origins in the composition of the United Nations Security Council, in which all five permanent members are nuclear weapons states. As chains of nuclear insecurity bind every nuclear weapon state to each other, unilateral nuclear disarmament remains a remote possibility. This is precisely where civil society and elected representatives can play a significant role in creating a favorable global discourse in an incremental manner.

Role of Civil Society

It is essential to create citizen platforms with broad-based participation to discuss issues of nuclear disarmament. Apart from sporadic movements against the acquisition of land for nuclear power plants, the public generally lacks awareness of the goals of global nuclear disarmament. For instance, South Asians Against Nukes, a platform for Indian and Pakistani citizens to keep abreast of nuclear dangers, was last updated in 2012, which speaks to the sorry state of cross-border dialogue on this issue. If citizens realized the consequences of a potential nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan, they might participate more vocally in a movement against nuclear weapons. There is a need to revitalize citizen participation in building a movement against nuclear weapons that counters each country’s security-oriented outlook.

Two workable proposals appear to be plausible. First, civil society must push for a collaborative campaign at UNESCO to ensure school syllabi globally incorporate the disastrous consequences of nuclear weapons on the ecosystem, food security, and human security. Second, nuclear weapon states should be persuaded to bind themselves in a lowest-common-denominator treaty preventing the offensive use of nuclear weapons. Meaningful UN reforms, the delinking of nuclear weapons as a source of great national pride and international status, along with citizen pressure on states to engage in disarmament talks may be the way forward for a nuclear weapon free world.

***

Image 1: David Hills via Getty Images

Image 2: Indranil Mukherjee via Getty Images