In the aftermath of the Pulwama attack in February of this year, both India and Pakistan carried out a series of maneuvers with grave escalatory risks. These included India’s employment of multirole Mirage-2000s to strike inside Pakistani territory and the deployment of nuclear submarines, accompanied by ambiguous official statements and the convening of a Nuclear Command Authority (NCA) meeting on the Pakistani side. And yet, Pakistani officials have confidently claimed that “nuclear deterrence remained intact during [the] post-Pulwama stand-off between Pakistan and India.” Here, nuclear deterrence remaining “intact” implies that the threat of nuclear use was (implicitly or explicitly) communicated. This clearly yet disturbingly indicates that Pakistan’s current approach to nuclear strategy—full-spectrum deterrence (FSD)—has a lower nuclear threshold embedded in it than may have been previously thought. This echoes back to another strategy of low threshold nuclear use, NATO’s flexible response strategy in Cold War era Europe.

It is this emulation that Sadia Tasleem and Toby Dalton have discussed in their recent article “Nuclear Emulation: Pakistan’s Nuclear Trajectory” in The Washington Quarterly, which highlights the limits of nuclear emulation in practice in the context of Pakistan’s FSD. The authors carried out an intensive analysis of the literature consumed and produced by Pakistani nuclear thinkers on nuclear doctrine, reflecting how deeply and thoroughly Pakistan’s strategic thought has embraced NATO’s flexible response strategy along with its inherent instabilities. The article raises important questions about the dangers of limited nuclear dialogue within Pakistan, and rightly suggests that the Pakistani strategic community might look to alternative models, including that of China, to improve its nuclear doctrine and strategy.

Emulation and Stability

The article raises important questions about the dangers of limited nuclear dialogue within Pakistan, and rightly suggests that the Pakistani strategic community might look to alternative models, including that of China, to improve its nuclear doctrine and strategy.

One of the key arguments made by Tasleem and Dalton is that Pakistan’s emulation of NATO’s nuclear policy “at the conceptual level, but less at the operational level” raises questions about the credibility of Islamabad’s nuclear strategy, a destabilizing factor for the management of South Asia’s security environment. It should be noted that the fact of younger nuclear states like Pakistan borrowing from Cold War deterrence literature is not an issue in its own right. However, the degree to which a country like Pakistan has learned from others’ experiences and innovated its own mechanisms and ideas to manage deterrence is a matter of grave concern, which Tasleem and Dalton highlight in the article. The authors effectively argue that Pakistan’s FSD doctrine is an emulation of NATO’s flexible response strategy of the 1960s, along with its inherent contradictions and challenges. FSD entails a “capability to deter all forms of aggression” at tactical, operational and strategic levels—a response based on the modernization of Indian strategic delivery systems, new developments in Indian missile defenses, and Indian warfighting strategies like the Cold Start doctrine.

Implications of the FSD doctrine include a central role for tactical nuclear weapons (TNWs). The discussion on TNWs by Tasleem and Dalton raises questions that require further research. For instance, as argued in the article, TNWs were developed to fill gaps in deterrence—but the question of whether these weapons have strengthened Pakistan’s fragile deterrence environment remains unanswered. For instance, the Nasr weapon system, a 60 kilometer short-range multi-tube ballistic missile with “shoot and scoot” capabilities, is a key delivery system of the FSD doctrine. Due to its short range, Nasr’s potential early and forward deployment in the battlefield for counterforce targeting would make it especially vulnerable to Indian attack, thus presenting Pakistan’s nuclear planners with a dangerous “use it or lose it” dilemma. Further study is required for a full understanding of how systems like Nasr play a role in Pakistan’s ongoing nuclear emulation.

The authors argue that FSD is ambiguous and potentially destabilizing due to “the lack of credible information about Pakistani operational practices” and the fact that a low nuclear threshold undermines strategic stability of the region. Taking a cue from Francis J. Gavin’s assessment of NATO’s flexible response during the 1960s, the dominant narrative of FSD and the lack of effort in exploring alternatives to it within Pakistan’s strategic community indicate: a) that FSD can be used to balance power dynamics within the country, as it helps sustain a dominant position for the military within a country’s national security agenda; and b) that FSD can be used as an attempt to strengthen and expand Pakistan’s conventional forces and raise the nuclear threshold gradually in future. Whether or not either aspect has been realized in Pakistan is a question for further research.

Alternative Models

A second argument made by Tasleem and Dalton is that this nuclear emulation has created a need for exploration of other ways to establish and maintain deterrence. There exists a stark disparity within the spectrum of views—between deterrence optimists and skeptics—in Pakistan’s literature on nuclear strategy. The deterrence optimist viewpoint that largely prevails in this literature, as the authors observe, is an emulation of Cold War concepts and is propounded by analysts with a background in Pakistan’s national security establishment and by government-funded research projects. This “narrower view of the fundamentals of [Pakistan’s] national security” underscores the increased salience of nuclear weapons and their effective deterrent capabilities. The recent statement from senior Pakistani officials that “nuclear deterrence remained intact during [the] Pulwama crisis” reflects this perspective.

This emulated Pakistani discourse, the authors argue, “underscores incentives for vertical proliferation that are based less on rational choice or strategic considerations than on a framing of threat perception dominated by an appropriated, Western logic”—that is, the logic “to procure and deploy ever greater numbers of nuclear weapons in order to keep pace with India’s rise.” This argument as it relates to incentives for vertical proliferation, however, is not fully developed. NATO’s flexible response strategy relied on continually improved weapons designs to establish the credibility of NATO’s doctrine at a high level of design reliability. Conversely, due to prevailing nuclear non-testing norms, Pakistan’s FSD is reliant on a one-time tested design, potentially raising further concerns about its credibility.

On the other hand, Tasleem and Dalton rightly pointed out that there exists little deterrence skepticism in Pakistan’s literature. It is important to explore this line of thought particularly today, when a fragile national economy has become a national security issue, raising critical questions of how much Pakistan can and must spend on defense, including its nuclear weapons arsenal. While it can be argued that an increase in deterrence skepticism may provide more space for conventional and emerging technologies to be built-up, this view might also lead to a lower reliance on high nuclear salience in Pakistan’s national security agenda and a higher reliance on diplomacy and engagement with multilateral nuclear arms control.

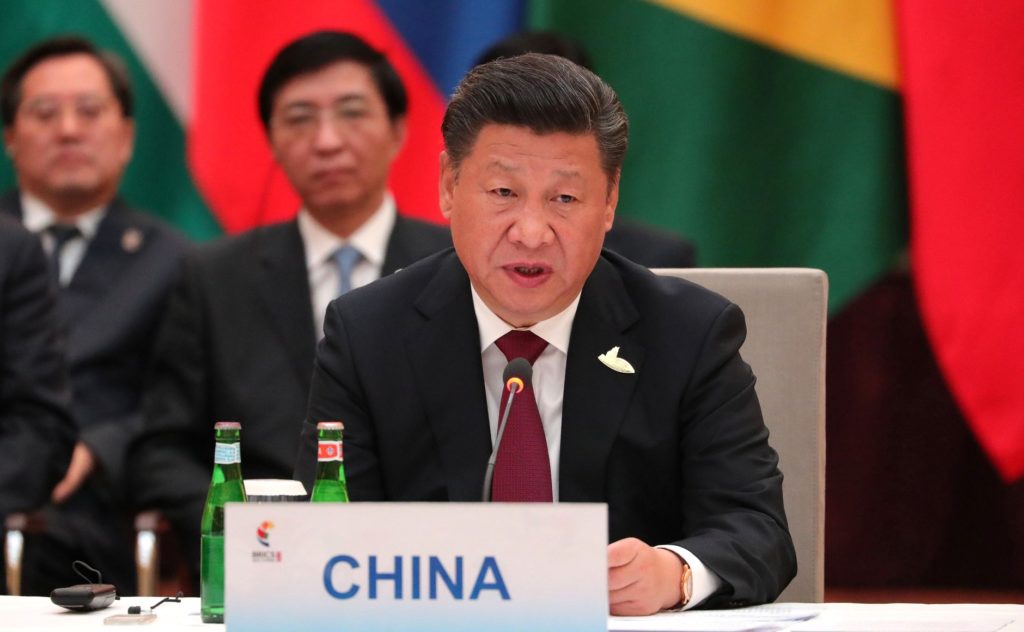

Looking to China?

The assumptions of rationality and restraint that prevail in Chinese deterrence strategy and posture are different from those that prevail in Pakistan’s India-centric deterrence strategy and posture. […] This is where the Chinese case study might serve as a role model.

Tasleem and Dalton suggest that engagement with Chinese deterrence policies could potentially help Pakistan explore an alternative for its deterrence posture. It should be noted that the assumptions of rationality and restraint that prevail in Chinese deterrence strategy and posture are different from those that prevail in Pakistan’s India-centric deterrence strategy and posture. The “madman” behavior sometimes attributed to Pakistan, an approach to coercive diplomacy intended to induce uncertainty in an adversary’s mind, may have served the strategic purposes of the Cold War. But in contemporary times of advanced technology and communications, it could prove detrimental. To deviate from this madman behavior, Pakistan requires revisiting its assumptions of rationality and restraint. This is where the Chinese case study might serve as a role model.

Building on the authors’ suggestion of Pakistan’s potential learning from a Chinese model, one can find three key lessons in the evolution of China’s nuclear doctrine for Pakistan. These lessons have helped China to strengthen regional and strategic stability, confidence in its nuclear force, and an image as a global power. First, Pakistan should strengthen a survivable, deliverable, and secure second-strike capability that will contribute to regional stability. This would help relieve Pakistan’s nuclear planners from “use it or lose it” pressures. Second, Pakistan could learn from China the strategic significance of no first use (NFU) of nuclear weapons and can start with extending a conditional NFU policy. This will augment stability by raising the nuclear threshold and reducing Pakistan’s strategic reliance on nuclear weapons. A visible, less ambiguous, and consistently restrained doctrine will also help Pakistan build its image as a responsible nuclear-armed state. Lastly, like Beijing, Islamabad should devise an economical and diverse conventional military strategy with increased stockpiling of conventional missiles that would aid in lifting the nuclear threshold in its regional theater of conflict.

Overall, the authors made a strong argument that Pakistan’s nuclear strategy emulates NATO’s flexible response strategy, along with its contradictions that raise challenges for the management of regional security. This requires that Pakistan begin to explore alternatives to Cold War and Western constructs in its nuclear planning. The authors draw attention to learning from NATO nuclear strategy from the 1960s onwards and allude to the option of emulating Chinese nuclear strategy as an alternative. The key arguments of the article raise further questions that, if and when explored, could provide all stakeholders a better understanding of Pakistan’s nuclear strategy—and move it toward an economical strategy aligned with Pakistan’s strategic needs based on a bias-free narrative and free from inherent unlimited risk tolerance. To take Pakistan out of its Cold War construct, the basic assumptions of rationality and restraint need to be revisited while responsibly keeping in view new and emerging technological developments.

Editor’s Note: In an ongoing series aimed at bridging the divide between policy analysis and academic scholarship, SAV contributors review recent articles and books published by leading scholars to evaluate the latest theoretical and analytical debates on strategic issues and their implications for South Asia. Read the series here.

***

Image 1: Picryl

Image 2: Wikimedia Commons